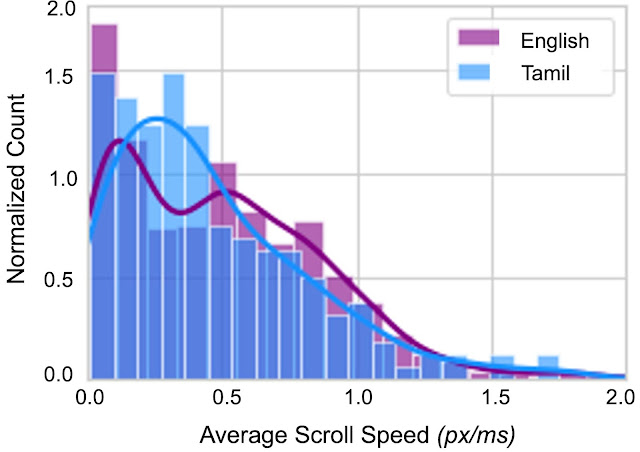

For many concepts, there is no direct one-to-one translation from one language to another, and even when there is, such translations often carry different associations and connotations that are easily lost for a non-native speaker. In such cases, however, the meaning may be more obvious when grounded in visual examples. Take, for instance, the word “wedding”. In English, one often associates a bride in a white dress and a groom in a tuxedo, but when translated into Hindi (शादी), a more appropriate association may be a bride wearing vibrant colors and a groom wearing a sherwani. What each person associates with the word may vary considerably, but if they are shown an image of the intended concept, the meaning becomes more clear.

|

| The word “wedding” in English and Hindi conveys different mental images. Images are taken from wikipedia, credited to Psoni2402 (left) and David McCandless (right) with CC BY-SA 4.0 license. |

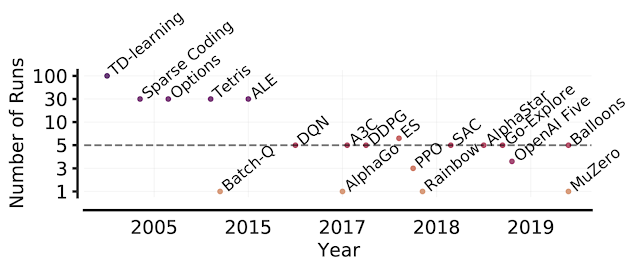

With current advances in neural machine translation and image recognition, it is possible to reduce this sort of ambiguity in translation by presenting a text paired with a supporting image. Prior research has made much progress in learning image–text joint representations for high-resource languages, such as English. These representation models strive to encode the image and text into vectors in a shared embedding space, such that the image and the text describing it are close to each other in that space. For example, ALIGN and CLIP have shown that training a dual-encoder model (i.e., one trained with two separate encoders) on image–text pairs using a contrastive learning loss works remarkably well when provided with ample training data.

Unfortunately, such image–text pair data does not exist at the same scale for the majority of languages. In fact, more than 90% of this type of web data belongs to the top-10 highly-resourced languages, such as English and Chinese, with much less data for under-resourced languages. To overcome this issue, one could either try to manually collect image–text pair data for under-resourced languages, which would be prohibitively difficult due to the scale of the undertaking, or one could seek to leverage pre-existing datasets (e.g., translation pairs) that could inform the necessary learned representations for multiple languages.

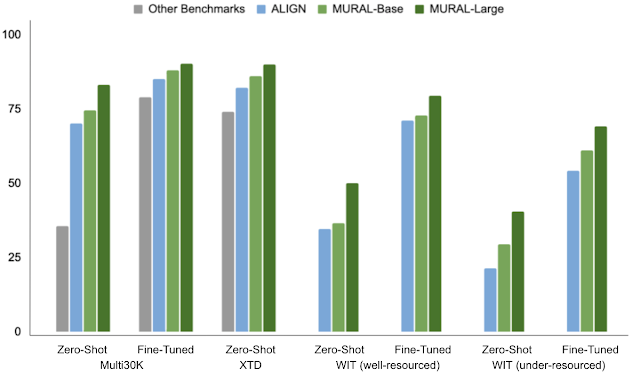

In “MURAL: Multimodal, Multitask Representations Across Languages”, presented at Findings of EMNLP 2021, we describe a representation model for image–text matching that uses multitask learning applied to image–text pairs in combination with translation pairs covering 100+ languages. This technology could allow users to express words that may not have a direct translation into a target language using images instead. For example, the word “valiha”, refers to a type of tube zither played by the Malagasy people, which lacks a direct translation into most languages, but could be easily described using images. Empirically, MURAL shows consistent improvements over state-of-the-art models, other benchmarks, and competitive baselines across the board. Moreover, MURAL does remarkably well for the majority of the under-resourced languages on which it was tested. Additionally, we discover interesting linguistic correlations learned by MURAL representations.

MURAL Architecture

The MURAL architecture is based on the structure of ALIGN, but employed in a multitask fashion. Whereas ALIGN uses a dual-encoder architecture to draw together representations of images and associated text descriptions, MURAL employs the dual-encoder structure for the same purpose while also extending it across languages by incorporating translation pairs. The dataset of image–text pairs is the same as that used for ALIGN, and the translation pairs are those used for LaBSE.

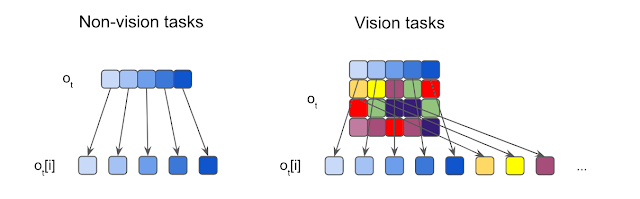

MURAL solves two contrastive learning tasks: 1) image–text matching and 2) text–text (bitext) matching, with both tasks sharing the text encoder module. The model learns associations between images and text from the image–text data, and learns the representations of hundreds of diverse languages from the translation pairs. The idea is that a shared encoder will transfer the image–text association learned from high-resource languages to under-resourced languages. We find that the best model employs an EfficientNet-B7 image encoder and a BERT-large text encoder, both trained from scratch. The learned representation can be used for downstream visual and vision-language tasks.

|

| The architecture of MURAL depicts dual encoders with a shared text-encoder between the two tasks trained using a contrastive learning loss. |

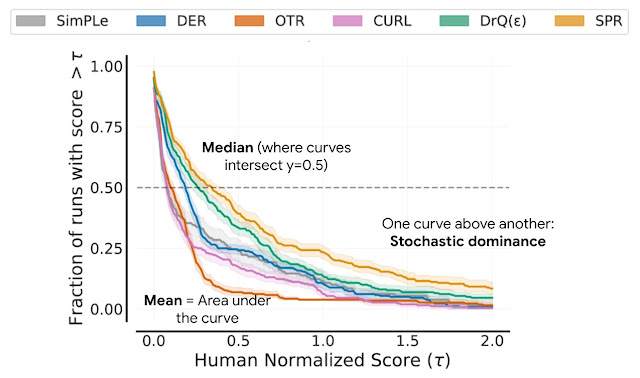

Multilingual Image-to-Text and Text-to-Image Retrieval

To demonstrate MURAL’s capabilities, we choose the task of cross-modal retrieval (i.e., retrieving relevant images given a text and vice versa) and report the scores on various academic image–text datasets covering well-resourced languages, such as MS-COCO (and its Japanese variant, STAIR), Flickr30K (in English) and Multi30K (extended to German, French, Czech), XTD (test-only set with seven well-resourced languages: Italian, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Polish, Turkish, and Korean). In addition to well-resourced languages, we also evaluate MURAL on the recently published Wikipedia Image–Text (WIT) dataset, which covers 108 languages, with a broad range of both well-resourced (English, French, Chinese, etc.) and under-resourced (Swahili, Hindi, etc.) languages.

MURAL consistently outperforms prior state-of-the-art models, including M3P, UC2, and ALIGN, in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings evaluated on well-resourced and under-resourced languages. We see remarkable performance gains for under-resourced languages when compared to the state-of-the-art model, ALIGN.

Retrieval Analysis

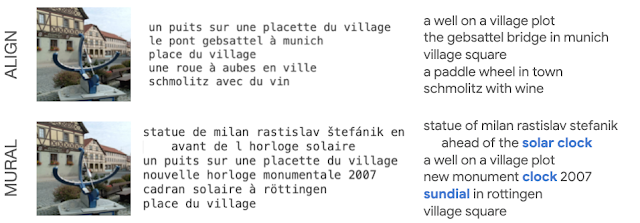

We also analyzed zero-shot retrieved examples on the WIT dataset comparing ALIGN and MURAL for English (en) and Hindi (hi). For under-resourced languages like Hindi, MURAL shows improved retrieval performance compared to ALIGN that reflects a better grasp of the text semantics.

|

| Comparison of the top-5 images retrieved by ALIGN and by MURAL for the Text→Image retrieval task on the WIT dataset for the Hindi text, एक तश्तरी पर बिना मसाले या सब्ज़ी के रखी हुई सादी स्पगॅत्ती”, which translates to the English, “A bowl containing plain noodles without any spices or vegetables”. |

Even for Image→Text retrieval in a well-resourced language, like French, MURAL shows better understanding for some words. For example, MURAL returns better results for the query “cadran solaire” (“sundial”, in French) than ALIGN, which doesn’t retrieve any text describing sundials (below).

|

| Comparison of the top-5 text results from ALIGN and from MURAL on the Image→Text retrieval task for the same image of a sundial. |

Embeddings Visualization

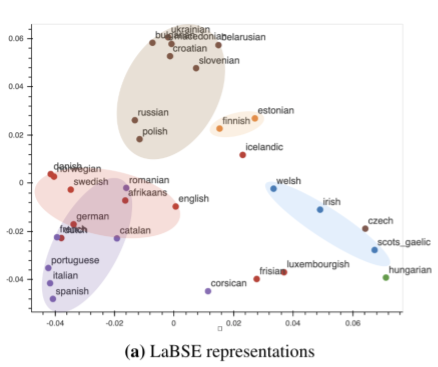

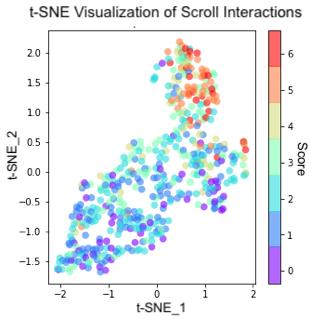

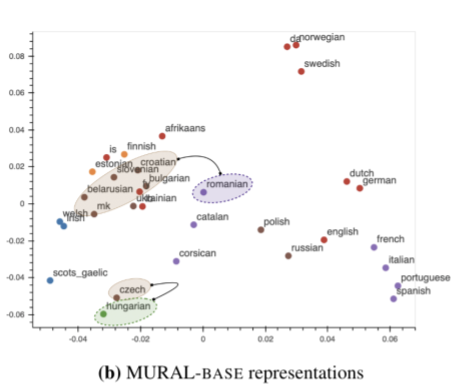

Previously, researchers have shown that visualizing model embeddings can reveal interesting connections among languages — for instance, representations learned by a neural machine translation (NMT) model have been shown to form clusters based on their membership to a language family. We perform a similar visualization for a subset of languages belonging to the Germanic, Romance, Slavic, Uralic, Finnic, Celtic, and Finno-Ugric language families (widely spoken in Europe and Western Asia). We compare MURAL’s text embeddings with LaBSE’s, which is a text-only encoder.

A plot of LabSE’s embeddings shows distinct clusters of languages influenced by language families. For instance, Romance languages (in purple, below) fall into a different region than Slavic languages (in brown, below). This finding is consistent with prior work that investigates intermediate representations learned by a NMT system.

In contrast to LaBSE’s visualization, MURAL’s embeddings, which are learned with a multimodal objective, shows some clusters that are in line with areal linguistics (where elements are shared by languages or dialects in a geographic area) and contact linguistics (where languages or dialects interact and influence each other). Notably, in the MURAL embedding space, Romanian (ro) is closer to the Slavic languages like Bulgarian (bg) and Macedonian (mk), which is in line with the Balkan sprachbund, than it is in LaBSE. Another possible language contact brings Finnic languages, Estonian (et) and Finnish (fi), closer to the Slavic languages cluster. The fact that MURAL pivots on images as well as translations appears to add an additional view on language relatedness as learned in deep representations, beyond the language family clustering observed in a text-only setting.

|

| Visualization of text representations of MURAL for 35 languages. Color coding is the same as the figure above. |

Final Remarks

Our findings show that training jointly using translation pairs helps overcome the scarcity of image–text pairs for many under-resourced languages and improves cross-modal performance. Additionally, it is interesting to observe hints of areal linguistics and contact linguistics in the text representations learned by using a multimodal model. This warrants more probing into different connections learned implicitly by multimodal models, such as MURAL. Finally, we hope this work promotes further research in the multimodal, multilingual space where models learn representations of and connections between languages (expressed via images and text), beyond well-resourced languages.

Acknowledgements

This research is in collaboration with Mandy Guo, Krishna Srinivasan, Ting Chen, Sneha Kudugunta, Chao Jia, and Jason Baldridge. We thank Zarana Parekh, Orhan Firat, Yuqing Chen, Apu Shah, Anosh Raj, Daphne Luong, and others who provided feedback for the project. We are also grateful for general support from Google Research teams.